By Anonymous

"Marijuana Uses - Dr. Lester Grinspoon's Marijuana Uses." 3 Sep. 2008

The author of this piece was, when he wrote it in the late 1990's, a 23-year-old graduate student and artist at a large university in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. He encounters the ocean of mind, first tentatively entering the realm, then embracing its many teachings.

I was twenty years old when I first smoked marijuana. I figured that I had already beaten the statistical odds, that I had jumped over the top of the bell curve, so there would be little harm if I took the plunge. The seed for my long-standing interest in drugs and non-ordinary states was planted early in my life, when I became a fan of Pink Floyd. I read volumes and volumes of literature about this band, particular information related to their enigmatic and tragic founder, Syd Barrett. He was, in the parlance of the day, an "acid casualty." Reading about Pink Floyd I was exposed to a great deal of writing concerning LSD and other psychedelic substances. As a youngster I was especially intrigued that one could ingest a minuscule amount of some simple chemical and have perception and cognition change so dramatically. Years went by and my interests became deeper and broader. When I encountered the writings of Terence McKenna, I simply knew this was the "path" (well, at least part of it) for me. Although to be frank, the thought of "altering my consciousness" was pretty frightening, there was still something drawing me towards psychedelics.

A very understanding friend of mine promised to help me out, but only with a slight qualification. He would procure some LSD for me, but only if I smoked marijuana first. He was NOT trying to push the drug on me. As he explained it, psychedelic states were almost unimaginable for those lacking the experience, but doubly so if one had never before chemically altered their consciousness via any means. The more I thought about it, the more sense his conditions made. I must qualify this by stating that throughout my youth, ingesting marijuana was not something I ever desired to do. Once, when I was in Tangier, Morocco, a young boy walked up to me and said "hashish?" I shot the boy a dirty look and he quickly scuttled away. For much of my life I probably equated it with snorting coke or shooting heroin. It seemed tacky, dangerous, and I just wasn't interested. After openly discussing marijuana with my friend, as well as others who actively smoked it, and after reading some non-political literature on the matter (such as that of Dr. Grinspoon) I realized my perception of marijuana was slightly askew, that this was not just another "demon drug," but a relatively safe plant, if used properly. So, one night I drove over to my friend's house with a pillow and a change of clothes, and we smoked marijuana.

Nothing happened that night. I was told to expect this, so I grudgingly accepted my friend's offer to try it again. Well, there was no mistaking it this time around. Needless to say, my second experience with marijuana got me high for the first time in my life, and I experienced it as a beautiful sensation, touching on the magical. I felt as though I was melting into not only whatever object I happened to be touching, but the environment as well. We were listening to the Harmonic Chant of David Hykes & The Harmonic Choir, and as I melted into the seemingly eternal flights of melody, I felt as though I had transcended time. It was amazing. The next morning I felt great, and we spent the day walking around the Mall in Washington, DC (sober), visiting many of the museums of the Smithsonian.

For the next year or so, I used marijuana approximately once a month, perhaps less. I still abstained from alcohol and tobacco, and I had yet to take the plunge with psychedelics. "Turning on" with marijuana made me hyper-aware of the different brain states I could potentially experience with different chemicals, and I realized I was still not ready for psychedelics. Eventually a time came when I felt ready to immerse myself in the ocean of mind, and when my first psychedelic experience was over with I graciously thanked my friend for his wisdom.

Over the years I've used marijuana, different patterns have come and gone. At times I would smoke it two or three times a month. At other times maybe once every two or three months. There were periods of three to four months during which I simply didn't smoke it. Period. I've had such a rich variety of experiences with marijuana that I could never fully describe them all.

Marijuana opened me up to the realm of the mind, of deeply experiencing and exploring the dimensions of consciousness available to me. In that regard, it has, with differing degrees of directness, led me into explorations of transpersonal psychology, mysticism, Sufism, shamanism, bodywork, and a host of other experiential/philosophical pursuits. When I got over the novelty of being stoned, I soon explored its effects more fully. I was amazed at what I found. Initially I would explore internal imagery, sharpening my visualization skills. Sometimes I would concentrate on feeling music more deeply. Other times I would simply think about the emotional and intellectual reactions of certain people to certain phenomena, particularly those reactions I found difficult to understand. Whilst stoned, I found it easier to put myself in the place of others. I could understand how people might believe any number of seemingly "irrational" or dense, impenetrable ideas. Marijuana opened me up to the existence of so many different views of the world, views I need not share to fathom and empathize with. I worked with my own feelings of sensuality/sexuality. I explored techniques of focusing my mind. I would meditate (in the Western, pre-Buddhist use of the word) upon religious/spiritual matters, clarifying things that seemed to make little to no sense in "sober" states of mind. How might this work? I don't know, but I have one idea that I often espouse. Our normal state of awareness is good for certain tasks, not for others. For example, one typically does not produce works of art in the same state of awareness that we use when driving about in our cars; an artist is instead focused inward, and on the outward projection of his/her internal state. In much the same way, such an internally-oriented state would be of little value in a sexual experience, in which humans exchange energy, moving and flowing together in a state of emotional and physical sympathy. What I find marijuana does is to shift the loci of my attention away from the mundane experiences and concerns that I, as an often automaton-like human, find myself dwelling on a moment-to-moment or daily basis. Instead, my mind is centered on matters that touch more on the extraordinary, those topics and experiences that are perhaps better left unexplored while driving along I-95 or working out my finances for the year. Those that view all of this as simply drug-induced illusions are sadly blind.

The greatest thing to come out of all of this is that I found these "stoned" experiences aren't as state-dependent as I initially believed. In the wake of my introduction and exploration of "stoned-mind awareness" I find that my appreciation for sensuality, aesthetics, and philosophy in "normal waking consciousness" (to quote James) has deepened greatly, almost to the point that I feel that the pre-drugs "me" was noticeably worse-off.

Some may wonder how my skills of empathy could possibly be improved by "smoking dope." Let me give you one recent example. For a period of a few months I found myself dwelling on religion-oriented topics, both stoned and otherwise. One night, in the midst of a marijuana-induced reverie, I got to thinking about the real person we call Jesus. These days, we think of him as some ethereal figure in some far off land shrouded in the historical mists of time. Just as then, people still believe that he was the Messiah, that he was the savior of mankind, that "in the Beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, the Word was God," and that Jesus was, quite literally, the "Word made flesh." I found myself imagining that at one time in history, this Jesus character was a living, breathing human like myself. Intellectually, I already knew this, but I increasingly felt as though I might be capable of fathoming what his disciples and apostles felt. His followers were in his presence, they looked into his eyes and heard his words and believed that they were looking at God. It was only in this state of consciousness that I could truly imagine what it might have been like to be in the presence of the this man and truly believe, and by extension, possibly experience what so many people on Earth experience during moments of great religious feeling and devotion. While I don't subscribe to the tenets of Christianity proper, I have come to understand how real it can all seem for people, and just how little such experiences are taken into account by those skeptics and atheists who argue against what they see as irrational beliefs. In this case, being stoned allowed my mind to circumvent its ordinarily non-religious bent, and if only for a few moments, come to know what the truly religious feel. As a consequence, I now offer this story (at least the aspect of Jesus as a man, and people looking into his eyes and believing in him) to people perplexed by religious belief in general, or Christianity in specific.

I hope this hasn't been too lengthy. I could write for days about marijuana, but I don't want to seem like a "drug preacher" or a "dope fiend." I hope it is apparent that marijuana has played a major role in my personal and intellectual development in the last few years, and this role has been nothing but positive (I now vaporize it, rather than smoke it, so I no longer ingest any carcinogens!). I thank God (or whatever force, conscious or not, responsible for existence) for the plant-human interaction known as marijuana intoxication.

Marijuana and its Meaning for Me

Posted by Knightkrm at 11:37 PM 0 comments

Labels: Lysergic acid diethylamide, Pink Floyd, Politics of the United States, Syd Barrett, Terence McKenna, United States, WASHINGTON, Washington DC

How Marijuana Ruined My Life

By Stephen Kessler

"Marijuana Uses - Dr. Lester Grinspoon's Marijuana Uses." 3 Sep. 2008

Stephen Kessler was born in 1947 in Los Angeles. He holds degrees in literature from Bard College and the University of California, Santa Cruz. He is the author of six books and chapbooks of original poetry and the translator of eight books of poetry and fiction from Spanish; his translations have appeared in The New Yorker, Harper's, the American Poetry Review, Mother Jones, Conjunctions, and many other magazines. His essays, criticism and journalism have appeared widely in the independent literary and alternative press since the early 1970s. He was a founding editor and publisher of small poetry presses Green Horse Press and Alcatraz Editions, the internal journal Alcatraz, and weekly newspapers the Santa Cruz Express and The Sun. Later he edited Outlook, a Mendocino County monthly. He makes his home on the coast of northern California, where he edits the Redwood Coast Review.

Sometimes I wonder what I might have amounted to if I hadn't become a pothead thirty years ago, when I was in graduate school, and pretty much remained one ever since. If not for marijuana, by now I'd probably be securely tenured in some English department and my mother would be able to brag to her friends about her son the doctor of philosophy. I'd be fluent in Academese, a respectable specialist in some form of critical theory, a teacher admired by his brightest students, a defeated imaginative writer, and a wretchedly unhappy and neurotic person. This, at least, is how I envisioned the path I was on at the time and where it must inevitably lead. Luckily, marijuana intervened.

Getting high, for me, in 1969, at the age of twenty-two, provided a vitally helpful perspective on the pettiness and irrelevance of an academic career to the creative vocation I felt was calling me. Following an acute psychotic episode-usefully assisted by psychedelic drugs, which triggered the explosion of all my internal conflicts and contradictions, I left the doctoral program and its generous fellowship for the full-time pursuit of my first love, poetry. This may not have been possible without a small but steady independent income that enabled me to live without a "real" job, but that financial independence was also existential in that the freedom it provided left me no excuses for not doing what I claimed to want to do, which was to write. Smoking marijuana gave me courage, at the time, to follow my deepest imaginative instincts, not only in the actual writing of poems but in the larger arena of making decisions about my life and how I wished to live it. Contrary to conventional wisdom, my judgment felt to me more fundamentally sound when I was stoned than straight.

Encouraged by the permission I felt to write without parental or professorial approval, I set out on the slow, uncertain, and mostly thankless path of the young poet, laboring over less-than-brilliant lines, writing, revising, sending the finished works to magazines, occasionally publishing, more often collecting rejections. Through most of this artistic apprenticeship I was accompanied by the sweet smell of burning hemp, whose presence surrounding my efforts seemed to expand the atmosphere of creative possibility, enhancing my sense of heroic romance on the seas of the blank page, that heady journey into the unknown. Frequently stoned as I indulged my imagination, I knew I was learning something about poetry, about writing, and about myself.

From there it was a slippery slope into the harder stuff: translation, criticism, journalism, editing and publishing. In the years since my earliest days as a dropout hippie poet I've managed to make a working life for myself in these various branches of literary practice, and while I wouldn't presume to credit pot for anything I've managed to accomplish, I do believe its companionship has helped me to maintain a certain equanimity amid the myriad distractions, confusions and aggravations of the surrounding world, enabling me to focus on what matters most, or what I most enjoy. If anything, marijuana has tempered my ambition, relaxing the compulsion to overachieve and giving license to play.

It is this sense of permission - or permissiveness, as the Virtue-pushers would have it - that makes the forbidden herb, for me, a useful antidote to the various societal prohibitions against, for example, "doing nothing." Pot reinforces my instinctive Taoism. Maybe that's why it's considered by some to be a dangerous drug: if everyone used it, nothing would get done. But paradoxical as it may seem, it is precisely when "doing nothing" that I tend to get the most accomplished as an artist. Or the deep involvement, the timelessness, experienced in the flow of creative activity may feel so aimless or effortless that it might as well be nothing, except for the fact that when I resume more consciously purposeful activity I often find persuasive evidence that I was doing something after all: a written text or other crafty artifact, a rack of freshly washed dishes, a stack of firewood, a pile of paid bills whose checks were written while listening to music or some radio show. Stoned or straight, I find these kinds of meditative activities to be a means of grounding myself in the mundane patterns and rhythms out of which imagination rises. The content, style and quality of what I write are not, I've found, especially affected by whether or not I've been smoking, but I am aware, when high, of more intimate sensuous relations with the language, with the texture of lines and sentences, with a kind of musical understanding not always readily evident to my more rational and sober self. The mild psychosis induced by this subtle alteration of consciousness may provide a different angle of vision, or revision, that can be of use in making esthetic decisions - what works and what doesn't, how to refine some detail, trim out the excess or develop some incomplete idea.

Obviously such working habits are more dependent on the mind and skill of the individual than they are on what drugs he may or may not be taking. An idiot on marijuana is still an idiot, possibly more so. And one's response to pot may vary greatly, depending on personality and circumstances. The health effects of smoking anything cannot be entirely positive, and I've seen enough stupid people in herbally induced stupors to be disabused of any evangelical notion of marijuana as a panacea. Like any other substance - food, tobacco, caffeine, alcohol, television - its abuse can be toxic and destructive. But unlike these ordinary and often insidious additives to daily life, pot remains not only legally prohibited but even now, at the turn of the millennium, socially stigmatized in a way that, say, coffee (a truly mind-altering substance) is not.

Among my friends, some smoke and some don't, for reasons of their own - just as I don't drink coffee because it makes my stomach jumpy - but the ones who do are just as productive in their lives and work and social contributions as are the abstainers. Anecdotally speaking, I've seen no correlation one way or another between marijuana use and creativity, citizenship, ethics or character. What I have noticed when smoking with friends is a ritual affirmation of time out, a refreshing pause in the everyday onslaught, a moment of quiet dialogue to savor, an island of sanity in the rush of events. Different people have different ways of relaxing, but those who habitually watch TV - whether in the lethargy of their own living rooms or in the noise and convivial drunkenness of a bar with ball games blaring - seem to me far more at risk for various psychopathologies than those who routinely prefer a few tokes of pot.

While I don't exactly take pride in my own habit, I don't consider it a major vice. A couple of puffs in midafternoon, following a late lunch, or at the end of a longish day, in the cocktail hour, or in the evening while listening to some especially beautiful music, strikes me as an eminently civilized way of decompressing the psyche. Whenever I find myself using it more than feels healthy - when I wake up in the morning foggyheaded, or feel a strain on my respiratory system - I may take a break for a few weeks as a way to remind myself of the drug's potentially negative effects and to refresh my appreciation of its positive ones. I wouldn't recommend it to anyone, especially children (I'm content with the knowledge that my eighteen-year-old daughter doesn't use it), but neither would I discourage the curious from trying it in a conscious, responsible way.

Partner, collaborator, accomplice, friend, companion - marijuana, over the years, has woven itself gently into the pattern of my life in a way that may have prevented me from pushing myself above and beyond whatever I've done as a writer. Without the benign corruption of pot, who knows, I might have been a contender. Instead, up to now, in my early fifties, I've managed to maintain my physical and mental health, create a few works I hope may be worth saving, cultivate many lasting friendships, and contribute what I could to my communities. For someone of alternately competitive and contemplative tendencies, the path I've taken, accompanied by the herbal reality-check of marijuana, feels to me thus far to have been a reasonable compromise. As my father used to say, "Everything in moderation."

Posted by Knightkrm at 11:32 PM 0 comments

Labels: Bard College, Cannabis, Los Angeles, Los Angeles California, Santa Cruz, University of California, University of California Los Angeles, University of California Santa Cruz

Office of National Drug Control Policy - Marijuana

Image via Wikipedia Office of National Drug Control Policy - Marijuana: "Marijuana

Image via Wikipedia Office of National Drug Control Policy - Marijuana: "Marijuana

Marijuana is a green, brown, or gray mixture of dried, shredded leaves, stems, seeds, and flowers of the hemp plant (Cannabis sativa). Cannabis is a term that refers to marijuana and other drugs made from the same plant. Other forms of cannabis include sinsemilla, hashish, and hash oil. All forms of cannabis are mind-altering (psychoactive) drugs.

Posted by Knightkrm at 11:25 PM 0 comments

Labels: Cannabis, Cannabis sativa, Drugs, Hashish, Health, Illegal, Office of National Drug Control Policy, Psychoactive drug

Marijuana and Music

Image by Getty Images via Daylife

Image by Getty Images via Daylife

Marijuana and Music

By Peter Webster

"Marijuana Uses - Dr. Lester Grinspoon's Marijuana Uses." 3 Sep. 2008

The author, who has reviewed for the International Journal of Drug Policy, is also the host of the Psychedelic Library web site(www.psychedelic-library.org). Noting the merits of practice with both music and the use of cannabis, he examines the cognitive mechanisms underlying the origins of jazz, while introducing us to the past times of Louis Armstrong and Mezz Mezzrow. We learn of the marihuana-using jazz musician round up of 1947 by the Bureau of Narcotics, both humorous and disturbing. In this cogent discourse on the origins of improvisation in jazz, he proposes that practiced, purposeful use of cannabis may provide a form of training in creative thinking that can be applied across many artistic and scientific fields.

One of the more remarkable effects noticed in the state of consciousness brought on by marijuana use is a greatly enhanced appreciation of music. The effect seems to be almost universal, and does not seem to fade with experience in the use of marijuana, as do certain other effects typically noticed by novice users. Curiously, such perception of enhancement does not seem to make excessive demands that the music to be appreciated be good, bad, or indifferent, although many persons originally interested only in pop music, for example, have suddenly found during a marijuana session that more "serious" music has quite unexpectedly become interesting in a way both surprising and profound. Conversely, a few who had previously rejected pop music as crude and trivial have come to appreciate it more through marijuana consciousness.

The resulting musical empathy is also quite durable, not requiring further marijuana sessions for its (at least partial) preservation, and so the net effect seems to be one of "opening up" a person to something he had merely ignored or overlooked. The enhanced appreciation is thus legitimized as something essential and "real" and not merely a "drug effect," something "artificial" that wears off with the waning of the changed conscious state. Marijuana consciousness thus seems to be a state in which at least a few of one's prejudices and predispositions may be temporarily suspended so that something long-ignored for whatever reason can be seen afresh, as if for the first time. And so it would seem that the marijuana experience can provide a kind of training that may subsequently help enlarge and enrich one's outlook in desirable and entirely voluntary ways.

Musicians (as well as other artists) have also testified not only to enhanced appreciation of music and art in general through the use of marijuana, but in addition some have insisted that these altered states of consciousness are useful and valuable to augment their creativity, although research verifying such claims is hard to accomplish in any meaningful or decisive way. Although it may also be somewhat speculative to say, it would seem that creativity would surely be boosted by an enhanced appreciation and a partial suspension of preconceptions, no matter what the stimulus.

Of course, as with so many things in life, practice makes perfect, or if not perfect, more nearly so. Thus it is with listening to music, and certainly with the making of music - a life-long process of practice - but more than a few puritanical minds will be bent out of shape by my suggestion, nay, my insistence, that the principle applies to the use of marijuana as well! It has long been obvious to me that many of the best minds of our time suffer from a ridiculous and self-imposed handicap by ignoring or even actively rejecting a great aid to thinking and creativity: the altered states of consciousness provided by marijuana and other age-old plant substances so revered by our forbears. They are tools both powerful and benign, both fickle and of great utility, and above all they require some considerable practice in order to use them in a way commensurate with their potential. Thus much of the research (on creativity, for example) which has used the substances on subjects who have not had long opportunity to practice with the resulting states of consciousness is rendered of limited value, and it won't be until these age-old aids to thinking and perception become once again widely used that we will begin to know their true usefulness. If they were universally revered by our tribal ancestors, and played an important role in the social and psychological evolution of our species as some researchers suspect, we may find them of even more value in a time when our technological powers have advanced maximally, but our moral sense of how to control great power for the common good has advanced little, if at all, since the bronze age.

As one who might have become a musician (had I practiced more!), and for whom music remains an irreplaceable source of inspiration, pleasure, consolation and communication, and also as one who has over the years had considerable practice in the use of the altered states of consciousness provided by marijuana and other such substances, I offer the following speculation about the nature of marijuana consciousness, its possible cognitive mechanisms, and music. The entire theory, if I may be allowed to call it that, has resulted from personal introspection about music and altered states and a selective use of technical knowledge gleaned from several sources. Study of relevant scientific material, due to its complex nature, has of course been done from the perspective of normal consciousness, but my evaluation of learned material has always involved considerable cross-examination from normal to altered states and back again. The speculative nature of what follows will certainly be seized upon by the puritanical as evidence that altered states of consciousness quite obviously lead to complete nonsense, but even altered states are no sure-fire remedy for narrow-mindedness.

Thanks to Prohibition, there has been insufficient serious research concerning the cognitive mechanisms and brain structures involved in the altered states of consciousness produced by marijuana and other such substances, and even research on the neurocognitive and psychological foundations of music, art and creativity has been frequently considered a study of the superfluous. Music and art for us moderns, unlike for our aboriginal ancestors, is seen as mere decoration, "entertainment," an activity of leisure and play (indeed, music is played), and our scientific institutions thus seem to believe that the study of such phenomena are of less importance than more "serious" studies. But from what limited scientific investigation as has been accomplished, it seems that both the making and perception of music involves the use of areas in the right hemisphere of the brain analogous to the speech and language comprehension areas of the left hemisphere - notably the famous Broca and Wernicke brain areas - and that these analogous right-brain areas might function similarly to the language centers of the left in the production, reading, and perception if not appreciation of music. Indeed, music seen as a linear symbolization comprised of sequential interrelated unitary elements describing a durational and holonomic conception seems an analogous phenomenon to language in many important ways. One may even surmise that music-making was very much a "language" for our earliest ancestors at a time when spoken descriptive language was merely in its most rudimentary and primitive state.

Now another of the most noticed effects of marijuana consciousness, and this effect is pronounced and very typical, is some change in the way we use short-term memory. Prohibitionists and others who mistrust not only marijuana consciousness but apparently even the idea that changed consciousness is something worthy of scientific study have seized on the short-term memory effect in their attempts to discredit marijuana use and strike terror into the hearts of marijuana users by implying that some kind of "permanent damage" must surely be happening when, in the middle of a sentence for instance, one forgets entirely what one was saying! But as all marijuana users know, if at this point one simply relaxes a bit, sure enough, the memory soon is re-established, indicating that what has happened is not a loss of short-term memory or a damaging of the brain structures mediating it, but a different manner of using it: perhaps we merely lose track of trains of ideas that are quite normally being recorded in short-term memory because our perceptions require far more attention than normally, i.e., our consciousness is heavily involved with other matters than mere utilitarian attention to continuity of logical or linguistic thought processes, our experience is so interesting and attention-consuming that we ignore, not lose, short-term memories. Indeed, the kind of short-term memory which scientists now study may be essentially a linguistic one, and other types of short-term memory, as yet unrecognized, may exist: they may be concerned with a more holonomic, rather than serially organized, linguistic way of contacting recent experience.

If this ignoring, or losing track of the mostly linguistic aspect of short-term memory is so universal, and the theory of music making and recognition being mediated by right-hemisphere areas analogous to those language-mediating areas of the left is valid, what happens to a musician when he plays music while under the influence of marijuana? Does he likewise forget what tune he is playing? Presumably if marijuana affects the language centers of the left hemisphere, even indirectly, it must similarly affect morphologically analogous structures of the right hemisphere. If marijuana consciousness does indeed affect a musician's perceptions and performance in some such way, how might that affect his music? And if a group or class of musicians who made a practice of using marijuana were so affected, how might that affect their collective concept of music and the way their music form developed? These might seem questions for research that in such a utilitarian age as our own will never be addressed. Yet perhaps the history of music already provides some hints.

The history of 20th Century music is a history, in one sense, of a bifurcation of music into two distinct ways of music-making. The long tradition of Western music has emphasized the importance of music composition and the notation of such compositions as opposed to the subsequent performance of these written compositions. The role of the composer and the performer are distinctly separate, and it is the composer, especially for orchestral works, who is considered to have done the lion's share of creating. The performer may "interpret" a written work of music with changes to tempo, dynamics, and general feeling, but any excess is considered bad form. All this of course has its parallel in language in the writing and reading of books. In our collective modern view, the greatest things that have been said are those written in stone, or at least in great books, and extemporaneous speech, as moving as it may be, is again, more often like entertainment than philosophy. When a piece of music has been composed, and when a linguistic expression has been written down, we seem automatically to attach more importance to it.

In the early decades of the 20th century however, the diverse influences in America, particularly of African origin, led to a form of music in which the performer himself took over the role of the composer to a significant extent, and jazz music became a form in which improvisation became the central aspect of the music, the performer himself spontaneously composing much of the ongoing structure of a piece being performed, guided by various conventions such as the repetition of a chord sequence, or the structuring of a solo line within a modal form, or other experimental structure. But in each case, it was the solo that became the central aspect of a piece, and the improvisation of a solo was (and is) expected to be unique, different in at least some ways than the performer's previous solos on the same tune or theme. The jazz solo expresses something new every time, something relevant to the current emotional and intellectual state of the musician-as-composer, and his interaction with his audience. The jazz solo became not only the central aspect of this music form, but came to resemble more and more the musical equivalent of an ancient linguistic form, story-telling, in which a performer takes an eternal theme and embellishes it for the present moment, for the benefit of his listeners, to make the universal history and mythology of the tribe manifest in the present and informative of current interests and concerns.

Was this 20th Century musical development merely a throwback to primitive forms by uneducated and underprivileged musicians who rejected Western traditions in music? Hardly. The great jazz musicians routinely know much about the traditions and technical structure of composed music to an extent that classical musicians envy. And the technical virtuosity of many jazz musicians often surpasses all normal requirements of the Western tradition:

- "There are many other instruments besides the trumpet which jazz musicians have made do the impossible. And they can play, for hours on end, technical, involved, difficult, educated lines that have melodic sense. They are all virtuosi. The same goes for string bass. The same goes for saxophone, although it is not used much in symphony. But anything Milhaud has done in classical music, McPherson and Bird, alone, do with ease as well as human warmth and beauty. Tommy Dorsey, for example, raised the range of the trombone two octaves. Britt Woodman raised it three. And take Jimmy Knepper. One of his solos was taken off a record of mine and written out for classical trombone in my ballet. The trombone player could barely play it. He said it was one of the most technical exercises he had ever attempted to play! And he was just playing the notes - not the embellishments or the sound that Jimmy was getting." (Charles Mingus, from the liner notes to his jazz album Let My Children Hear Music, Columbia KC 31039.)

In the 1930s and 1940s, the very period in which improvisation in jazz was becoming the central creative aspect of the music, jazz musicians almost universally enjoyed marijuana, and we have many personal attestations and historical documents to prove the case. One particularly rollicking book about the epoch, and the wild times and great music that resulted, is Mezz Mezzrow's Really the Blues, and Mezz was himself not only a great jazzman, but famous for the excellent quality marijuana he seemed always to have a large supply of! A reading of personal reflections about the use of marijuana by jazzmen of the time indicates that the herb was often used as a stimulus to creativity, at least for practice sessions, many such as Louis Armstrong praising its effects highly. The widespread use of marijuana by jazz musicians of the time is even revealed by the campaign of Harry Anslinger and his Bureau of Narcotics to demonize marijuana, and one of the reasons ol' Harry thought important was that the "evil weed" was being used by jazz musicians. At one point he issued a directive to all his field agents, as related in the following story from a speech by Charles Whitebread, Professor of Law, USC Law School:

- After national marijuana prohibition was passed, Commissioner Anslinger found out, or got reports, that certain people were violating the national marijuana prohibition and using marijuana and, unfortunately for them, they fell into an identifiable occupational group. Who were flouting the marijuana prohibition? Jazz musicians. And so, in 1947, Commissioner Anslinger sent out a letter, I quote it verbatim, "Dear Agent So-and-so, Please prepare all cases in your jurisdiction involving musicians in violation of the marijuana laws. We will have a great national round-up arrest of all such persons on a single day. I will let you know what day." [From The History of the Non-Medical Use of Drugs in the United States by Charles Whitebread. A Speech to the California Judges Association 1995 annual conference].

Is it possible to attach some correlation between the cognitive effects of marijuana we are now becoming scientifically aware of and the development of creative jazz forms of the 1930s and 1940s? To return to my previous question, if high on marijuana does a performing musician "lose track" of the composition he is playing much as one might lose track of the thread of a conversation under marijuana influence?

In fact, experienced marijuana users who are well aware of the "short-term memory effect" become quite adept at counteracting it; in all probability extensive practice with marijuana consciousness allows the user to not only counteract such effects but use them in positive ways. A temporary and momentary "forgetting" of the limiting structures of either an ongoing conversation, or of a musical piece, when such an effect has been practiced with, might well be just the right influence to bring improvisation to the fore, both in music and conversation or writing. It is my view, therefore, that the cumulative and long term practiced use of marijuana by virtuosi jazz musicians was a certain and positive factor in the evolution of the music towards improvisation as its central and most creative aspect.

Now my experience with music indicates that it would of course be silly to say that jazz musicians of the 1930s were literally forgetting what tune they were playing, and through such constant forgetfulness arose a great musical innovation! But as with the practiced user of marijuana who learns to counteract the short-term memory effect and use it to advantage, I would more realistically propose that a similar thing was happening collectively and incrementally within the fairly small community of jazz musicians of the time, a community more like a family than a world-wide diversity of people and schools as it has become today. The jazz community of the time constantly practiced together, brainstormed together, performed together, and smoked marijuana together. As a cumulative effect, it is my contention that the practiced use of marijuana provides a training that assists the improvisational, creative frame of mind much as other kinds of study or training shape abilities and perfect talents. It is not that marijuana consciousness itself "produces" ideas that are creative, or that valuable ideas come from the experience or during it, but that cumulatively, over time, the kind of perception and thinking initiated by marijuana leads one to be generally more open to alternative and perhaps adventurous ways of seeing things which enrich normal consciousness. Normal consciousness, as we all admit, is limited in often involuntary, invisible ways by our times, customs, prejudices, by the necessary ignorances we must cultivate to cope with modern life. Marijuana very probably contributed to, or was used as a tool to facilitate the jazz revolution in music, and might be similarly used to facilitate important advances in any other area of human interest where creativity and adventurous thinking is important. The understanding of human consciousness and the nature of altered states of consciousness comes immediately to mind!

And as for literally forgetting what piece one is playing, biographies of great musicians often tell of experiences when they were required to bluff it through with some extemporaneous inventions. The great French jazz pianist Martial Solal tells of such a concert he gave in his youth. It was to qualify for a prize and at the climax of the classical piece he was playing his mind went blank, but his forced improvisation was so good that the judges didn't even detect his bluff! It was at that point, he says, that he decided that jazz rather than classical music was to be his future.

So perhaps jazz musicians literally did often encounter some short-term memory effects, and had often to "bluff" it. With virtuoso musicians, such bluffing is unlikely to fall into something less than proficiency, and from what experienced users of marijuana all say, the "bluffing" seems to result in an unprecedented creativity: in a sort of Zen way, what comes out of the virtuoso when he abandons his calculated intentions is not nonsense but often his finest creation! If a mere plant can assist the forgetfulness which is the germ of spontaneous creativity, the greatest minds of our time surely ARE missing the boat by rejecting not only its use but by assisting to prevent others from doing so. They thus prove once again that even genius is capable of the narrowness thought characteristic of the uneducated.

Posted by Knightkrm at 11:21 PM 1 comments

Labels: Altered state of consciousness, Cannabis, Consciousness, Louis Armstrong, Mezz Mezzrow, New Orleans Louisiana, Research, Scientific method

Ritalin

Ritalin

Methylphenidate (Ritalin) is a medication prescribed for individuals (usually children) who have an abnormally high level of activity or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). According to the National Institute of Mental Health, about 3 to 5 percent of the general population has the disorder, which is characterized by agitated behavior and an inability to focus on tasks. Methylphenidate also is occasionally prescribed for treating narcolepsy.

Health Effects

Methylphenidate is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant. It has effects similar to, but more potent than, caffeine and less potent than amphetamines. It has a notably calming effect on hyperactive children and a "focusing" effect on those with ADHD.

Recent research1 at Brookhaven National Laboratory may begin to explain how methylphenidate helps people with ADHD. The researchers used positron emission tomography (PET - a noninvasive brain scan) to confirm that administering normal therapeutic doses of methylphenidate to healthy, adult men increased their dopamine levels. The researchers speculate that methylphenidate amplifies the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter, thereby improving attention and focus in individuals who have dopamine signals that are weak, such as individuals with ADHD.

When taken as prescribed, methylphenidate is a valuable medicine. Research shows that people with ADHD do not become addicted to stimulant medications when taken in the form prescribed and at treatment dosages.2 Another study found that ADHD boys treated with stimulants such as methylphenidate are significantly less likely to abuse drugs and alcohol when they are older than are non-treated ADHD boys.3

Because of its stimulant properties, however, in recent years there have been reports of abuse of methylphenidate by people for whom it is not a medication. Some individuals abuse it for its stimulant effects: appetite suppression, wakefulness, increased focus/attentiveness, and euphoria. When abused, the tablets are either taken orally or crushed and snorted. Some abusers dissolve the tablets in water and inject the mixture - complications can arise from this because insoluble fillers in the tablets can block small blood vessels.

Trends in Ritalin Abuse

At their June 2000 meeting, members of NIDA's Community Epidemiology Work Group (CEWG)* shared the following information.

The abuse of methylphenidate has been reported in Baltimore, mostly among middle and high schools students; Boston, especially among middle and upper-middle class communities; Detroit; Minneapolis/St. Paul; Phoenix; and Texas.

When abused, methylphenidate tablets are often used orally or crushed and used intranasally.

In 1999, 165 methylphenidate-related poison calls were made in Detroit; 419 were reported in Texas, with 114 of those involving intentional misuse or abuse.

On Chicago's South Side, some users inject methylphenidate (this is referred to as "west coast"). Also, some mix it with heroin (a "speedball") or in combination with both cocaine and heroin for a more potent effect.

Because stimulant medicines such as methylphenidate do have potential for abuse, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has placed stringent, Schedule II controls on their manufacture, distribution, and prescription. For example, DEA requires special licenses for these activities, and prescription refills are not allowed. States may impose further regulations, such as limiting the number of dosage units per prescription.

Be especially scrutinizing as you determine the drug rehab program that meets your specific needs. This site has listings of drug rehab programs and treatment centers, alcohol rehabilitation programs, teen rehabs, sober houses, drug detox and alcohol detox centers.

Please call (866) 762-3712 to find the right drug rehabilitation center for you or your loved one.

"Ritalin Addiction Drug Rehab Ritalin Drug Rehabilitation Prescription Drug Addiction Treatment Centers." 3 Sep. 2008

Posted by Knightkrm at 7:55 PM 0 comments

Labels: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Controlled Substances Act, Medication, Mental Health, National Institute of Mental Health, Ritalin, Stimulant

Marijuana Brain Scans Prove Damage

Image via Wikipedia Marijuana Brain Scans Prove Damage Anti-Marijuana Video PSA. The effects on the brain from substances like alcohol, cocaine, heroin, and marijuana are shown in brain scans. Studying the effects of drugs and alcohol on the brain has clearly been one of the most informative and fascinating parts of my work. I had a sense growing up that drugs and alcohol weren't helpful to my overall health. I might add, this notion was helped along by getting drunk on a six pack of Michelob and half a bottle of champagne when I was sixteen years old - I was sick for three days. After that, I've been lucky enough to stay away from drugs and alcohol. After doing this work there's no way you could get me to do marijuana, heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, LSD, PCP, inhalants or any more than a glass or two of wine or beer. These substances damage the patterns in your brain, and without your brain you are not you. There is really quite a bit of scientific literature on the physiological effects of drugs and alcohol on the brain. SPECT has demonstrated a number of abnormalities in substance abusers in brain areas known to be involved in behavior, such as the frontal and temporal lobes. There are some SPECT similarities and differences between the damage we see caused by the different substances of abuse. There tends to be several similarities seen among classes of abused drugs. The most common similarity among drug and alcohol abusers is that the brain has an overall toxic look to it. In general, the SPECT studies look less active, more shriveled, and overall less healthy. A "scalloping effect" is common amongst drug abusing brains. Normal brain patterns show smooth activity across the cortical surface. Scalloping is a wavy, rough sea-like look on the brain's surface. I also see this pattern in patients who have been exposed to toxic fumes or oxygen deprivation. My research assistant says that the drug brains she has seen look like someone poured acid on the brain. Not a pretty site. SPECT can be helpful in evaluating the effects of drugs and alcohol on the brain. On 3D surface images several substances of abuse appear to show consistent patterns. For example, cocaine and methamphetamine abuse appear as multiple small holes across the cortical surface; heroin abuse appears as marked decreased activity across the whole cortical surface; heavy marijuana abuse shows decreased activity in the temporal lobes bilaterally and heavy alcohol abuse shows marked decreased activity throughout the brain. These findings tend to improve with abstinence, although long term use has been associated with continued SPECT deficits seen years after abstinence. SPECT can be helpful in several ways in drug and alcohol abuse. First, 3D surface SPECT images of drug and alcohol abusers can be used in drug prevention education. Second, SPECT studies can help break though the denial that often accompanies substance abuse. When one is faced with their own abnormal cerebral perfusion it is hard to remain in denial. Third, SPECT may help evaluate if there is an underlying neuropsychiatric condition that needs treatment. Marijuana usage typically causes decreased activity in the posterior temporal lobes bilaterally. The damage can be mild or severe, depending on how long a person used, how much use occurred, what other substances were used (nicotine is a powerful vasoconstrictor) and how vulnerable a particular brain is. For more information see Dr. Amen's article High Resolution Brain SPECT Imaging in Marijuana Smokers with AD/HD, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, Volume 30, No. 2 April-June 1998. Pgs 1-13. Producer: AEGIS; Production Company: AEGIS; Keywords: drug addiction, substances abuse, alcoholism; Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs from www.archive.org.

Image via Wikipedia Marijuana Brain Scans Prove Damage Anti-Marijuana Video PSA. The effects on the brain from substances like alcohol, cocaine, heroin, and marijuana are shown in brain scans. Studying the effects of drugs and alcohol on the brain has clearly been one of the most informative and fascinating parts of my work. I had a sense growing up that drugs and alcohol weren't helpful to my overall health. I might add, this notion was helped along by getting drunk on a six pack of Michelob and half a bottle of champagne when I was sixteen years old - I was sick for three days. After that, I've been lucky enough to stay away from drugs and alcohol. After doing this work there's no way you could get me to do marijuana, heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, LSD, PCP, inhalants or any more than a glass or two of wine or beer. These substances damage the patterns in your brain, and without your brain you are not you. There is really quite a bit of scientific literature on the physiological effects of drugs and alcohol on the brain. SPECT has demonstrated a number of abnormalities in substance abusers in brain areas known to be involved in behavior, such as the frontal and temporal lobes. There are some SPECT similarities and differences between the damage we see caused by the different substances of abuse. There tends to be several similarities seen among classes of abused drugs. The most common similarity among drug and alcohol abusers is that the brain has an overall toxic look to it. In general, the SPECT studies look less active, more shriveled, and overall less healthy. A "scalloping effect" is common amongst drug abusing brains. Normal brain patterns show smooth activity across the cortical surface. Scalloping is a wavy, rough sea-like look on the brain's surface. I also see this pattern in patients who have been exposed to toxic fumes or oxygen deprivation. My research assistant says that the drug brains she has seen look like someone poured acid on the brain. Not a pretty site. SPECT can be helpful in evaluating the effects of drugs and alcohol on the brain. On 3D surface images several substances of abuse appear to show consistent patterns. For example, cocaine and methamphetamine abuse appear as multiple small holes across the cortical surface; heroin abuse appears as marked decreased activity across the whole cortical surface; heavy marijuana abuse shows decreased activity in the temporal lobes bilaterally and heavy alcohol abuse shows marked decreased activity throughout the brain. These findings tend to improve with abstinence, although long term use has been associated with continued SPECT deficits seen years after abstinence. SPECT can be helpful in several ways in drug and alcohol abuse. First, 3D surface SPECT images of drug and alcohol abusers can be used in drug prevention education. Second, SPECT studies can help break though the denial that often accompanies substance abuse. When one is faced with their own abnormal cerebral perfusion it is hard to remain in denial. Third, SPECT may help evaluate if there is an underlying neuropsychiatric condition that needs treatment. Marijuana usage typically causes decreased activity in the posterior temporal lobes bilaterally. The damage can be mild or severe, depending on how long a person used, how much use occurred, what other substances were used (nicotine is a powerful vasoconstrictor) and how vulnerable a particular brain is. For more information see Dr. Amen's article High Resolution Brain SPECT Imaging in Marijuana Smokers with AD/HD, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, Volume 30, No. 2 April-June 1998. Pgs 1-13. Producer: AEGIS; Production Company: AEGIS; Keywords: drug addiction, substances abuse, alcoholism; Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs from www.archive.org.

Posted by Knightkrm at 10:36 AM 0 comments

Labels: Addiction, Alcoholism, Creative Commons, Drug abuse, Drug addiction, Health, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, Substance Abuse

America's Never-ending Prohibition: from Reuters News

America's Never-ending Prohibition: from Reuters News

by Bernd Debusmann (12 Aug, 2008)

| It seems only the White House and law enforcement want drug prohibition to continue

On the contrary. Since 1937, the year marijuana was outlawed, its use in the United States has gone up by 4,000 percent, according to the Marijuana Policy Project, a Washington-based lobby group which advocates regulating the drug similar to alcohol. A recent World Health Organization study of marijuana use in 17 countries placed Americans at the top of the list. The 1920-1933 prohibition on the sale, production and transportation of alcohol is now seen as a dismal failure of social engineering. Will the prohibition on marijuana ever be seen in a similar light? For the first time in a generation, there is a bill before Congress that would eliminate federal penalties "for the personal use of marijuana by responsible adults." But not even the congressman who introduced the bill, Democrat Barney Frank, sees bright prospects for swift passage. The last time the U.S. Congress dealt with legislation that would have decriminalized marijuana was in 1978, when a bill introduced by Senator Edward Kennedy was passed by the Senate but never got to a vote in the House. The case for legalizing marijuana, the most widely used drug after alcohol and tobacco, rests on several planks - the most obvious being that prohibition simply hasn't worked despite extraordinarily labor-intensive and costly government efforts. In 2006, the last year for which figures from the Federal Bureau of Investigation are available, 830,000 Americans were arrested on marijuana charges, most of them for possession rather than trafficking. That works out at a marijuana arrest every 38 seconds. A study last year estimated the cost of these arrests at $10.7 billion. "This is an enormous waste of law enforcement resources that should be focused on violent and serious crime," says Allen St. Pierre, who heads the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), the marijuana smokers' lobby in Washington. "With alcohol we acknowledge the distinction between use and abuse, and we focus our law enforcement on efforts to stop irresponsible use. We do not arrest or jail responsible drinkers. That should be our policy for marijuana as well." The Bush administration's drug czar, John Walters, will have none of this. He talks about marijuana in terms reminiscent of the apocalyptic warnings issued by Harry Anslinger, the first head of the Bureau of Narcotics in the 1930s and a driving force behind the 1937 marijuana prohibition. Anslinger deemed marijuana "an addictive drug which induces in its users insanity, criminality and death." Walters often takes issue with "the perception that marijuana is about fun and freedom. It isn't. It's about dependency, disease and dysfunction." (For a vivid portrayal of the dysfunction Walters warns about, see a mock documentary produced for the White House Office of National Drug Policy. It is entitled Stoners in the Mist, a play on the 1988 film on mountain gorillas in the Congo.) Americans who have admitted smoking marijuana at one point or another but escaped dependency, disease and dysfunction include President George W. Bush, Supreme Court Judge Clarence Thomas, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, Senator John Kerry, former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, former Vice President Al Gore and Barack Obama, the Democratic nominee for next November's presidential election. Former President Bill Clinton falls into a special category. When he studied in England, away from the long reach of U.S. law, he experimented with marijuana "a time or two," he once told a television interviewer. "I didn't inhale and I didn't try again." Hollywood, conscious of a mass audience that does inhale, has produced a slew of new "stoner" movies this year. The pot-smoking protagonists include an investment banker and a medical student (Harold & Kumar), a psychiatrist (The Wackness), and a process server (Pineapple Express). But sympathetic portrayals of marijuana use in popular culture do not necessarily translate into faster progress towards legalization. Government anti-drug fighters are serious in their opposition. When Barney Frank, at a news conference to explain the rationale for his bill, was asked what timeline he had in mind, he quipped: "Not soon ... but eventually, you'll see the development of a marijuana futures market." David Murray, the chief scientist in the drug czar's office who had listened to the briefing, was not amused. "It's not funny," he said, "not funny at all." But not impossible either, in the long run. - Article from Reuters, August 6th 2008 - You can contact the author at Debusmann@Reuters.com |

Posted by Knightkrm at 10:25 AM 0 comments

Labels: Barack Obama, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Federal government of the United States, George W. Bush, John Kerry, Marijuana Policy Project, U.S. Congress, United States

Legalize All Drugs by John Stossel on Creators.com - A Syndicate Of Talent

Legalize All Drugs by John Stossel on Creators.com - A Syndicate Of Talent: "The other day, reading the New York Post's popular Page Six gossip page, I was surprised to find a picture of me, followed by the lines: 'ABC'S John Stossel wants the government to stop interfering with your right to get high. … The crowd went silent at his call to legalize hard drugs' (http://tinyurl.com/6af6gv).

I had attended a Marijuana Policy Project event (www.mpp.org) celebrating the New York State Assembly's passage of a medical-marijuana bill. (The bill hasn't passed the Senate.) I told the audience I thought it pathetic that the mere half passage of a bill to allow sick people to try a possible remedy would merit such a celebration. Of course medical marijuana should be legal. For adults, everything should be legal. I'm amazed that the health police are so smug in their opposition.

After years of reporting on the drug war, I'm convinced that this 'war' does more harm than any drug.

Independent of that harm, adults ought to own our own bodies, so it's not intellectually honest to argue that 'only marijuana' should be legal — and only for certain sick people approved by the state. Every drug should be legal.

'How could you say such a ridiculous thing?' asked my assistant. 'Heroin and cocaine have a permanent effect. If you do crack just onc"

Posted by Knightkrm at 10:24 AM 0 comments

Labels: Cocaine, Hard and soft drugs, John Stossel, Marijuana Policy Project, Medical cannabis, New York Post, New York State Assembly, War on Drugs

Drugs - A comparison

Drugs - A comparison: "Drugs - A comparison

This table was converted from the Hash Info Museum original to HTML by Captain Acid."

Posted by Knightkrm at 10:22 AM 0 comments

How to Stop Emotional Eating | Health, Fitness, Exercise, and Weight Loss (66 pounds in 17 weeks)

Image via Wikipedia How to Stop Emotional Eating | Health, Fitness, Exercise, and Weight Loss (66 pounds in 17 weeks): "For many of us, it is a natural reaction to turn to food when we are upset, happy, sad or depressed. Over time, this reaction becomes a learned activity that we resort to without even realizing it. Whether your parents used food rewards when you were growing up or you learned the behavior on your own, emotional eating can really derail your diet plans. However, there are ways that you can overcome this issue and get back on track for healthy eating."

Image via Wikipedia How to Stop Emotional Eating | Health, Fitness, Exercise, and Weight Loss (66 pounds in 17 weeks): "For many of us, it is a natural reaction to turn to food when we are upset, happy, sad or depressed. Over time, this reaction becomes a learned activity that we resort to without even realizing it. Whether your parents used food rewards when you were growing up or you learned the behavior on your own, emotional eating can really derail your diet plans. However, there are ways that you can overcome this issue and get back on track for healthy eating."

Posted by Knightkrm at 10:20 AM 0 comments

Labels: Compulsive overeating, Diet, Eating, Health, Healthy diet, Nutrition, Shopping, Weight Loss

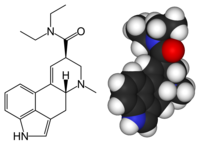

Ecstasy: Neurotoxicity and How It Can Be Reduced

Image via Wikipedia

Image via Wikipedia

Molly Flannagan

Ecstasy (MDMA) has become a drug of choice among 18-25 year olds (2), and its effects on behavior and neurotoxicity merit the attention of this class. Ecstasy use has become fairly widespread on college campuses and in rave and nightclub settings. This paper will look at the mechanism through which MDMA acts, its neurotoxicity, and how users can reduce risk involved with ecstasy use.

How does ecstasy work?

Ecstasy alters behavior by increasing serotonin levels in the brain. It accomplishes this by altering the neurotransmitter serotonin's reuptake process. (6) In the normal serotonin system, a serotonin neuron will receive a signal from a neighboring nerve cell to release vesicles of serotonin into the synaptic cleft. The post-synaptic cell (which has the appropriate receptors for serotonin) then picks up the molecule. When the serotonin binds to the receptor, it causes an electric signal to change the membrane permeability which causes changes in the body. When a vesicle of serotonin is released, most of the molecules are pulled back into the pre-synaptic cell. This process of drawing serotonin back into the original neuron for it to be reused is called reuptake. When MDMA is present in the system, however, it interferes with the natural process by preventing the serotonin from entering at the reuptake site. This causes an excess of serotonin in the system, which creates the feelings of euphoria associated with MDMA. (1)

Just how neurotoxic is ecstasy?

Users of MDMA are quick to praise the psychological effects of the drug, but the effects on their physical health can be detrimental. Studies show that heavy, prolonged use of MDMA can significantly reduce the number of serotonin transporters which are necessary to bring the neurotransmitter back to the neuron from which it was released. Studies supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) showed that MDMA damages neurons that release serotonin, and that heavy MDMA users have lingering memory problems for at least two weeks after stopping the drug. In the first study, researchers used positron emission tomography (PET) to compare the brains of MDMA users who had abstained from all psychoactive drugs for three weeks and people who had never used MDMA. They found that the amount of MDMA used was directly linked to the number of serotonin transporters remaining. They also found that the degree of memory impairment is based on the amount of MDMA used. (3)

How can the neurotoxic effects of ecstasy be reduced?

Pre- and Post-loading can be used to lessen the harmful effects of MDMA. Pre-loading is taking supplements before rolling to help counteract the neurotoxic effects of ecstasy. A common pre- load consists of 200mg of 5-Hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), up to 100mg of Vitamin B-6, up to 1000mg of Vitamin C, and 100mg of Magnesium. (3) Adding more serotonin to the system can counteract the mechanism through which MDMA damages nerve cells. 5-HTP is the direct precursor to serotonin, and can therefore combat the neurotoxicity of MDMA. Vitamin B-6 helps to convert 5-HTP into serotonin, thereby boosting its effect. Because MDMA is thought to be neurotoxic due to oxidized free radicals, the consumption of the anti-oxidant Vitamin C can also reduce the harmful effects of MDMA. Magnesium is used as a muscle relaxer to minimize involuntary jaw-clenching associated with ecstasy use. A post-load consists of the same supplements except that magnesium is unnecessary. (4) It is also beneficial to drink water during and after the use of ecstasy.

How does it all fit together?

Ecstasy has been proven to be neurotoxic when heavy doses are used frequently. However, it also appears that a moderate use of the drug, combined with harm-minimizing supplements can help to counter the negative effects associated with it. Ecstasy has become one of the most popular drugs among college-age students, and its popularity shows no sign of decreasing. As a result, it is critical for users to be informed of the risks involved and how they can reduce these risks.

WWW Sources

1) Ecstasy.org2) National Institute on Drug Abuse

5) Rave Safe

Comments made prior to 2007

After reading the article Ecstasy: Neurotoxicity and How It Can Be Reduced by Molly Flannagan I have one question. Is it suggested that a person using ecstasy take a pre-load as well as a post-load or is it suggesting to take supplements either before or after and not both times? If you did take supplements before AND after ecstasy use would you be overloading your system with vitamins? Would this be dangerous? ... Melody, 24 May 2006

"Ecstasy: Neurotoxicity and How It Can Be Reduced | Serendip's Exchange." 2 Sep. 2008

Posted by Knightkrm at 1:03 AM 0 comments

Labels: Drug abuse, Drugs, Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Neuron, NIDA, Psychoactive drug, Substance Abuse

Alcohol, tobacco more harmful than cannabis, LSD, ecstasy: study

| |||||||||||||||||

|

|  | |||||||||||||||

Posted by Knightkrm at 12:52 AM 0 comments

Labels: Britain, England, Illegal drug trade, Lysergic acid diethylamide, Medical Research Council, Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, United Kingdom, University of Bristol

Ecstasy approved for medical study

| |

| ||

Ecstasy approved for medical studyWASHINGTON (CNN) --A South Carolina psychiatrist said Wednesday he will immediately start recruiting patients after winning approval to conduct the first study testing MDMA -- better known as ecstasy -- as a therapeutic tool. Dr. Michael Mithoefer plans to conduct psychotherapy sessions with 20 women who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder due to sexual assaults or other violence, and who haven't been helped by other treatment. Twelve of the women will receive MDMA prior to the sessions while eight will be given a placebo. The Food and Drug Administration approved Mithoefer's protocol in 2001, but it took another two years to find an institutional review board willing to sanction the study, which is a required step when dealing with human research subjects. Mithoefer's research required approval from the Drug Enforcement Administration because MDMA is a Schedule I drug. It's grouped with drugs like heroin, cocaine and LSD, all considered to have no medical use. Bill Grant, a spokesman for the DEA, said the final approval came Tuesday night. Mithoefer says he works with post-traumatic stress disorder patients all the time and he's excited about the possibility of finding a better treatment for the hundreds of thousands of Americans who suffer from the sometimes debilitating disorder. "We owe it to them," he said. "It would be irresponsible for the medical community not to investigate something like this." At the same time, he warns that using MDMA in an uncontrolled setting can be very dangerous. "It's really important for people to realize the fact that we have permission to do this study and we can do it safely in this setting," he said. Also, the fact that he's received permission for the study, he said, "does not mean that you can use ecstasy safely and anywhere." MDMA was first invented in 1912 but largely ignored until young people made it a recreational drug starting in the late 1970s. Psychiatrists quickly became aware of its unusual properties, and several dozen experimented by giving MDMA to patients -- including people suffering post-traumatic stress disorder -- and others with intense anxiety after receiving diagnoses of terminal cancer. One of those patients from the early 1980s is an artist now living in the western United States, who spoke with CNN. She did not want her name used. After being raped and beaten at age 17, the woman suffered severe panic attacks for eight years, leading to three hospitalizations before being treated with MDMA. Before those sessions, she said her trauma was misdiagnosed as schizophrenia, severe depression and bipolar disorder. "MDMA allowed me, for the first time, to sit with the details of the event, and separate them from what was happening in the present," she told CNN. "I was able to relax my body. I was able to say, 'this is not happening to you right now.' " Suicidal at the time, she said the treatment may have saved her life. "There might have been another way, but the way that I see it is that I probably would have died," she said. "When someone is traumatized, walls form around trauma -- like a scar -- and it's hard to get someone to open up and talk about it," explains Dr. Julie Holland of New York University, author of "Ecstasy: A Complete Guide." "What's unique about MDMA is that it's actually stimulating but decreases anxiety," Holland told CNN. "It could help people feel calm and comfortable enough to explore painful things that are hard to talk about." "A good analogy is that it would give psychiatry something akin to anesthesia during therapy," she said. "And unlike anesthesia, your memory is completely intact, but even enhanced. You remember the trauma very clearly, but are comfortable enough to talk about it." "Because it anesthetizes the patient to some extent," Holland said, "you can get to that malignant core in one or two sessions instead of three or four years." But Dr. Scott Lillienfeld, a psychiatrist at Emory University who has studied post-traumatic stress disorder, said that hypothesis is "at the least, muddled." Lillienfeld said effective treatment actually requires the patient to face their trauma head-on. "If you're calm, you're not getting at the root of the problem," said Lillienfeld. He also said Mithoefer's study has methodological problems. "There's no real placebo," he said. "Everyone will know who's on the drugs. What I wonder is, instead of a placebo, why aren't they giving a drug that mimics the physical effects?" Mithoefer said all participants will have to undergo psychiatric screening and a physical exam to ensure they don't have any physical risk factors. Ecstasy, a strong stimulant, is thought to be particularly dangerous to people with high blood pressure. It also has been known to cause dangerous overheating in people who take it and then exercise or dance for a long period of time. Patients in this clinical trial will be given the drug only one or two times. They will be under a doctor's supervision for the entire time they are under the drug's influence. Mithoefer said he hopes to begin the actual therapy sessions next month. CNN producers Caleb Hellerman and Miriam Falco contributed to this report. |

| |

| Find this article at: http://www.cnn.com/2004/HEALTH/02/25/ecstasy.study/index.html |

| |

|

Posted by Knightkrm at 12:51 AM 0 comments

Labels: Anxiety, Bipolar disorder, Controlled Substances Act, Drug Enforcement Administration, Major depressive disorder, Posttraumatic stress disorder, United States, WASHINGTON

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=06c9d7d6-9902-49c7-b3b4-94089c789e54)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=d2285bf8-ac29-4e6e-9f2a-5aad6e995990)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=2db163df-269b-4e37-af47-9367a2a82817)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=7e4099f1-71a7-42c3-ad32-b655aef0cd8f)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=4f4aed40-beeb-4f6f-a4fa-980965799238)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=b3a1d212-4a8a-40b3-b9a0-7fba7182a915)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=55e447e3-bb5e-4f1b-87e6-ee7b71b08061)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=b2eed7f7-2d20-456f-a242-6537583ec047)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=20e8d2eb-f235-4c69-b328-ee3fdfda0635)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=b7b93241-c809-4e05-aad7-d828ad189788)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=98a9c1dc-82eb-4e3e-8a58-9edb3ee9533f)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=8e026fe8-b8db-47d7-8d5c-6388c297d117)